The Spotlight is a monthly summary that encapsulates some of the more notable media experiences I’ve had over the past thirty days. From insights on games played, to articles worth checking out, and even cool stories from tabletop role-playing games, it all has a place in the Spotlight.

For the month of May, 2024, here’s what I’m shining the spotlight on.

Games

Star Wars Jedi: Survivor

Star Wars Jedi: Survivor successfully builds upon the excellent narrative and solid mechanics put forward by its predecessor, Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order in every way, save for its technical performance. That poor performance is such an overwhelmingly negative force in this game, that it nearly stopped me from continuing on several times. But I stuck with it and saw it through to the end, and for my troubles I was rewarded with a pretty great Star Wars story, that while predictable at times, still managed to surprise me.

I don’t have too much to say about Star Wars Jedi: Survivor without delving into spoilers, but I will say that this sequel plays far more into the power fantasy of being a Jedi than its predecessor did. If Fallen Order was about the protagonist learning how to be a Jedi and coming into their powers, Survivor is about them not letting that power consume them.

I just wish that Star Wars Jedi: Survivor wasn’t so buggy — both in terms of performance and in terms of that one terrible spider enemy that camouflages itself before pouncing at you. I hate that thing.

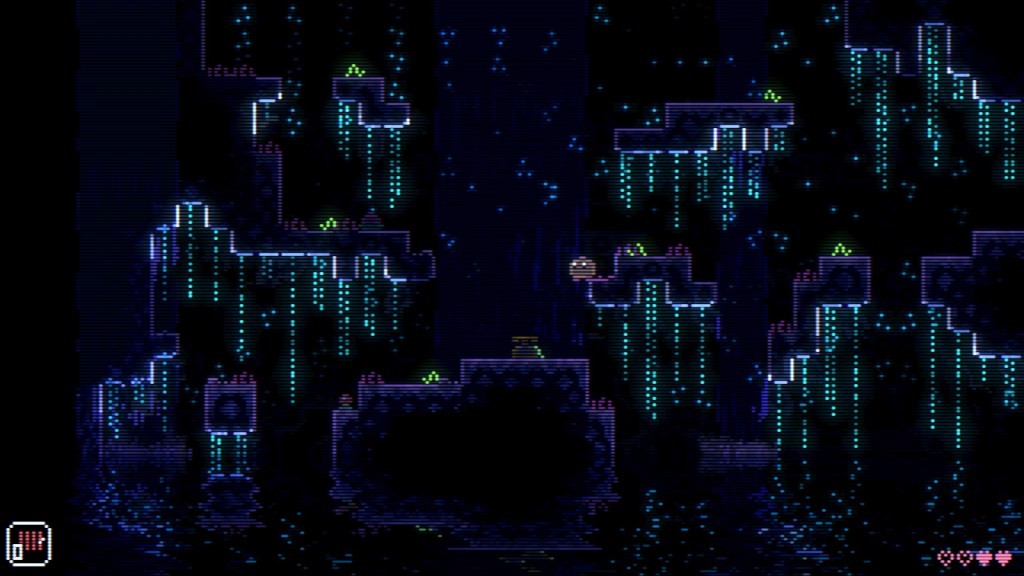

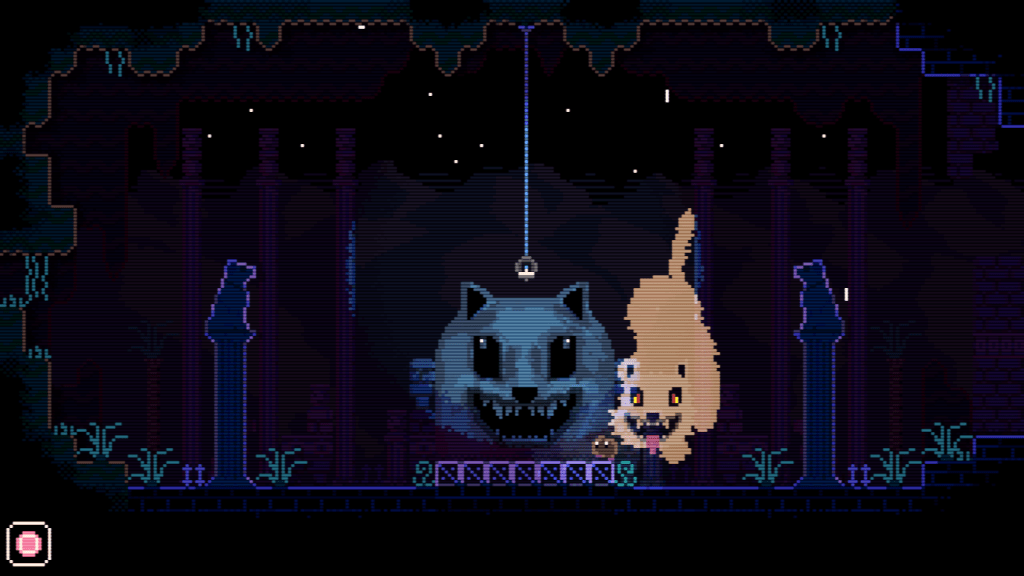

Animal Well

I wrote a whole thing about Animal Well, so I encourage you to read my expanded thoughts on it there. The short version, however, is that I was unimpressed by Animal Well early on, but it slowly revealed itself to be one of the most intriguing games I’ve ever played, even if it left me with infinitely more questions than answers.

Little Kitty, Big City

Little Kitty, Big City is a rare games that’s nice and relaxing while also offering just enough mechanical density to keep you hooked with engaging gameplay. Despite some rough edges, Little Kitty, Big City is a delightful game that fans of platformers and animal hijinks shouldn’t miss out on.

You play as the titular “little kitty,” and you need to get back to your home which just so happens to be in a high-rise apartment building. To accomplish that, you’ll have to help a whole cast of animal characters out with their problems, from a forgetful duck that keeps misplacing their ducklings, to an enterprising tanuki with a penchant for crafting wacky inventions, one of which being your ability to fast-travel.

Little Kitty, Big City is platformer (catformer?) at its core, requiring you to poke in every nook and cranny you can find, pick up every collectible or shiny object you can see, and simply interact with everything that you can. While it’s a lot of fun and incredible low-stakes, the platforming mechanics don’t work especially well when you’re trying to navigate tight spaces. Leaping up staggered air conditioners to reach the top of a building is good idea in theory, but much like a cat the camera tends to do its own thing and complicates the issue.

None of my nitpicks are strong enough to dampen my positivity for Little Kitty, Big City, however. I think it’s a fantastic little game that scratches my itches for both a low-stakes cozy game, and a platformer with lots of bits and bobs to snatch up. It’s a lot of fun and is oozing with charm, and I think it’s well worth your time.

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

I’m a few years late to the party, but I finally got around to playing Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice just in time for its long-awaited sequel to finally drop. But based on my short time with this entry, I don’t think I’ll ever finish this game, let alone play its sequel.

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice is a third-person action game that’s absolutely beautiful to behold, but doesn’t offer much more beyond its aesthetic beauty. I found it to be extremely boring, which is a pretty damming thing to say about a game with a six hour runtime. I’ve often heard that the story of Hellblade was the real star of the show, but I didn’t find it engaging enough to outweigh the issues I had with it.

Chief among those issues was that every mechanic and creative decision felt half-baked, often resembling a first draft of something more engaging. The enemies you fight are just as uninspired as the moves that Senua could pull off, making combat feel very receptive from the earliest parts of the game.

I could handle simple combat were it not for the constant recycling of puzzles, though. All you’re ever tasked outside of combat are basic perspective puzzles that require you to seek the shape of a glyph out among the environment, just like something you’d see in the early stages of The Witness. You do that a couple of times between fights with some bad guys, then a boss shows up, and that’s it.

I guess people must have really jived with Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice‘s story or something, because I do not understand why this game is so beloved. It’s boring and repetitive, and my understanding is that the sequel is just more of that. It’s an absolute stunner with its visuals, but I found it to be thoroughly non-engaging.

Deadpool

Talk about a time capsule. Deadpool is a game that initially came out on the Xbox 360, and boy is it a product of its time. The humor is dated, but I bet some comic fan out there is all about having words like “shitballs” and “chimichangas” yelled at them and considers it, “very character appropriate.”

Humor and story aside, however, it’s just not an exceptionally fun game to play in 2024. It’s dated in every conceivable way, and honestly, doesn’t deserve to be judged by modern standards. Even so, I’m glad I was able to rent a copy of this from my local library, which is a whole other discussion for later in this Spotlight, rather than track down a copy on my own.

Chants of Sennaar

Like Animal Well before it, Chants of Sennaar is the hot and new puzzle obsession in my household. It has been the catalyst for several discussions about the intent behind the written languages of the many fictional cultures in the game, and has truly been one of the best bonding activities we’ve partook in.

But what is Chants of Sennaar? Chants of Sennaar is a puzzle game that sees your character traversing a massive city-sized tower that’s comprised of different cultures with different values, priorities, and most importantly, different languages. Ascending to the top of the city requires you to pass through the various levels, where you’ll need to learn the languages within in order to find any success.

I won’t say too much more because I plan on writing up a piece for Chants of Sennaar in the coming weeks, but simply put, I really love this game. It has its faults that make certain sections a bit more laborious than you’d like, but overall it’s a massive hit in our home, and would have easily cracked last year’s Game of the Year list.

Watch List

Manifest

I can’t remember the last time I watched something out of spite before Manifest. I only bring this show up because of how much time we spent watching the entirety of this piece of garbage, but I urge you to not watch any of it. Or do what you want, it’s your life.

The cool elevator pitch for this show is that a plane in 2013 took off from Jamaica and was bound for New York. The plane hit some wild turbulence and once cleared, was diverted to land elsewhere in upstate New York, where it’s revealed that it’s now 2018. The plane vanished and resurfaced 5 years later, and now its passengers are trying to rebuild their lives and understand the voices they all now have in their heads.

Sounds pretty cool, right? Three or four episodes in, however, it sure felt like the elevator pitch was all the show runners had conceived and were figuring it out as they went. Things go so far off the rails in its unnecessarily convoluted story, with plot points introduced and immediately forgotten about at a staggering pace. All of that is made even more obvious in the presence of some world class over acting. Netflix categorizes this one as a soap opera, and that description could not be more accurate.

If you’re like me and enjoy making fun of bad television to soften the blow of having to suffer through it, you’re going to fucking adore Manifest. But if you actually wanted to see if this cool elevator pitch lands the plane (pun very intended), I’ll save you the time: it doesn’t.

The Hairy History Of 6 Forgotten Planet Of The Apes Games

When I saw this video pop up on my feed, it struck me that I could not name one Planet of the Apes game. Finding out that there were at least six of them was very surprising. After watching this video, however, I understand why I’ve never heard of them.

X-Men ’97

I don’t think that I’ve enjoyed any piece of X-Men media as much as I did the first season of X-Men ’97. Aside from reminding me that I need to go back and complete the original series, X-Men ’97 kept me gripped from start to finish, thanks to its stellar story lines and gorgeous animation.

If I were to nitpick (and I will), I’d say that the story gets a bit bogged down mid-season, and some of the voice acting is downright bad in places, both in terms of performance and in audio quality. But these are minor gripes that don’t overshadow of the overwhelming excellence of the series. Not having watched the original series beforehand, I did feel a bit out-of-the-loop at times, but it was pretty easy to figure out what was happening as long as you have a base understanding of the core conflict behind the X-Men and mutants alike.

If you like the X-Men, you should watch this show. If you aren’t a huge fan of the X-Men, you should still watch this show, because it might be the thing that wins you over. I’ve never been a huge fan of the X-Men, but I absolutely loved X-Men ’97 despite that fact, and I think you will too.

Listening Party

It Never Stops – Bad Books

Even Rats – The Slip

Known By None – Medium Build

The Rest

The Master of Disaster – Big Hits

The Master of Disaster returns at last to discuss beating the living shit out of my player’s characters, and how doing so made for some of the most engaging D&D content we’ve had in a while. This article also goes into the narrative and mechanical considerations around combat scenarios, which sounds obvious, but is something I’ve struggled with in the past.

The Incredible Enigma of Animal Well

My partner and I fell in love with Animal Well and its many, many secrets. We also discovered that puzzle games are a very serious, very satisfying, and sometimes very contentious genre of game in this house.

News

Microsoft Shutters More Studios

I love video games as a product and absolutely hate the industry that creates them, because they pull shit like what Microsoft just pulled, all the time. It’s even more brutal when you consider that developers are often exploited due to their love of the product they’re working on, meaning that they’re likely more willing to accept less pay just to work on stuff they enjoy.

Couple that with cold hard capitalism, and you get instances like this where Microsoft shuts down several studios at once, and hundreds of people are just out on their asses in an industry that’s somehow so profitable, but so volatile. This is bullshit as is, but it’s even worse when you see that Microsoft praised HiFi Rush for being a “break out hit,” but closed the studio anyway.

It’s moves like this that should make anyone considering doing business with Xbox hesitate. If I was running an indie studio that Xbox wanted to absorb, I’d be a lot more wary of that offer after seeing that making good games aren’t enough to save you from being shut down.

There’s a lot I could say about this whole mess beyond what I already have, but just know that it’s all garbage and I hate it.

IGN Consumes More Outlets

The Imagine Games Network has gobbled up some international outlets, such as Gamesindustry.biz and Eurogamer, along with the rest of the Gamer network. I suspect that IGN’s international stuff just isn’t as popular outside of the US, which explains why you buy these big international organizations.

I doubt that fans of those publications will see any real difference in content strategies or whatever, but anything could happen. I included this news story mostly because I think it’s important to take note when news outlets start to consolidate. Sure, the stakes are way lower in the games industry, but you never know, a directive from high up could result in all outlets publicly praising Mario Party, and we just can’t have that.

Thanks for checking out The Spotlight. We’ll be back at the end of June with another installment. Consider subscribing to The Bonus World so you can get an email updating you whenever we publish something new.