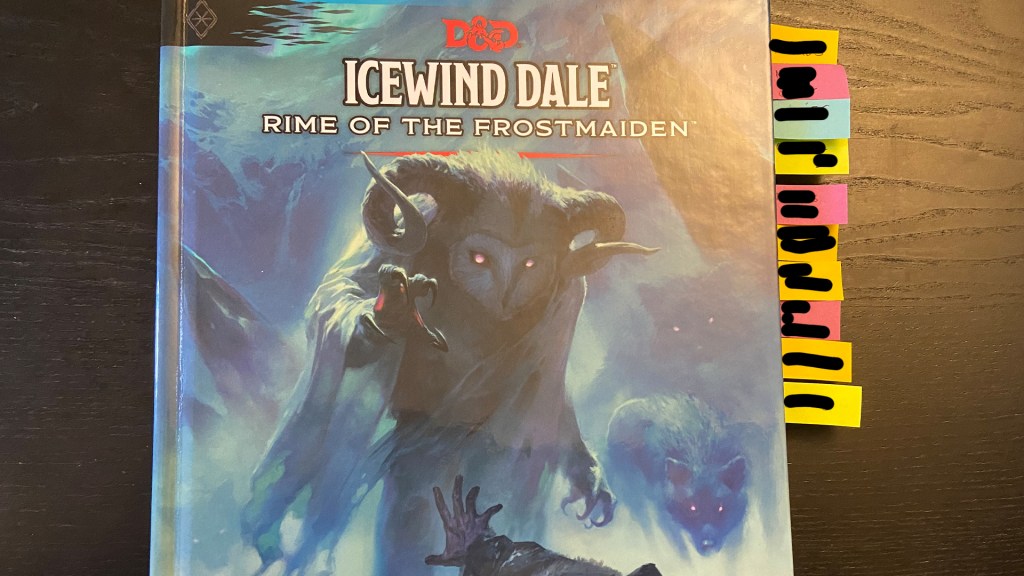

One of the most interesting, fun and tedious parts about being a Dungeon Master is preparing from session to session, but even more of a challenge is preparing a new campaign entirely. My group and I are currently wrapping up our “one-shot” of The Sunless Citadel, a pretty decent Dungeons & Dragons adventure, and are gearing up for our next big campaign. As luck would have it, Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden released just as we were finishing up, so we decided that it would be our next adventure. Being that this is my first time prepping a full campaign, I figured I do it as meticulously as possible. Here’s what’s happened.

Considering I’ve always had some difficulty with absorbing the things I read, I had to approach preparing for Rime of the Frostmaiden from an overly redundant and thorough angle. I can’t just read something once or twice and commit it to memory. My brain just never worked like that so I had to bust out old my note-taking methods from my school days in order to properly tackle this behemoth of a book. What that meant was that I had to essentially read the book paragraph by paragraph, rewriting everything I was reading into a notebook.

The notes themselves, while useful, aren’t really why I’m doing all of this extra busy work. The problem I have is that I need to rewrite something to commit it to memory. I don’t think that’s too uncommon, but it definitely adds a lot more time and effort to whatever it is I’m trying to absorb. But I wanted to be as meticulous as possible, and luckily the book is actually really interesting which has fueled me to continue with this overly redundant way of learning.

Both my notebook and the module itself have tiny little bookmark tabs everywhere that denote all of the important information I might need at a moments notice. I do it in a way that is more granular than the format of the book itself can account for allowing me to quickly access anything from notable characters, town lore, quests, items, hazards and more. On top of that, my notes also point me to whichever page in the book I need to get to, so I’m covering all of my bases to make sure I am never more than a few pages away from relevant information my players might need.

But I don’t want to paint all of this as an exercise in futility or anything, because I’m genuinely enjoying the book on its own. The story in Rime of the Frostmaiden is interesting and captivating as written, and all of my efforts in documenting it are just so I can provide my players with the best campaign I can muster. I get to enjoy the book as is, but my players are relying on me to deliver them an exciting and cohesive story to go along with the actual game itself. If I don’t nail this thing then they might have a pretty lackluster impression of the module, and that would be upsetting on a lot of levels.

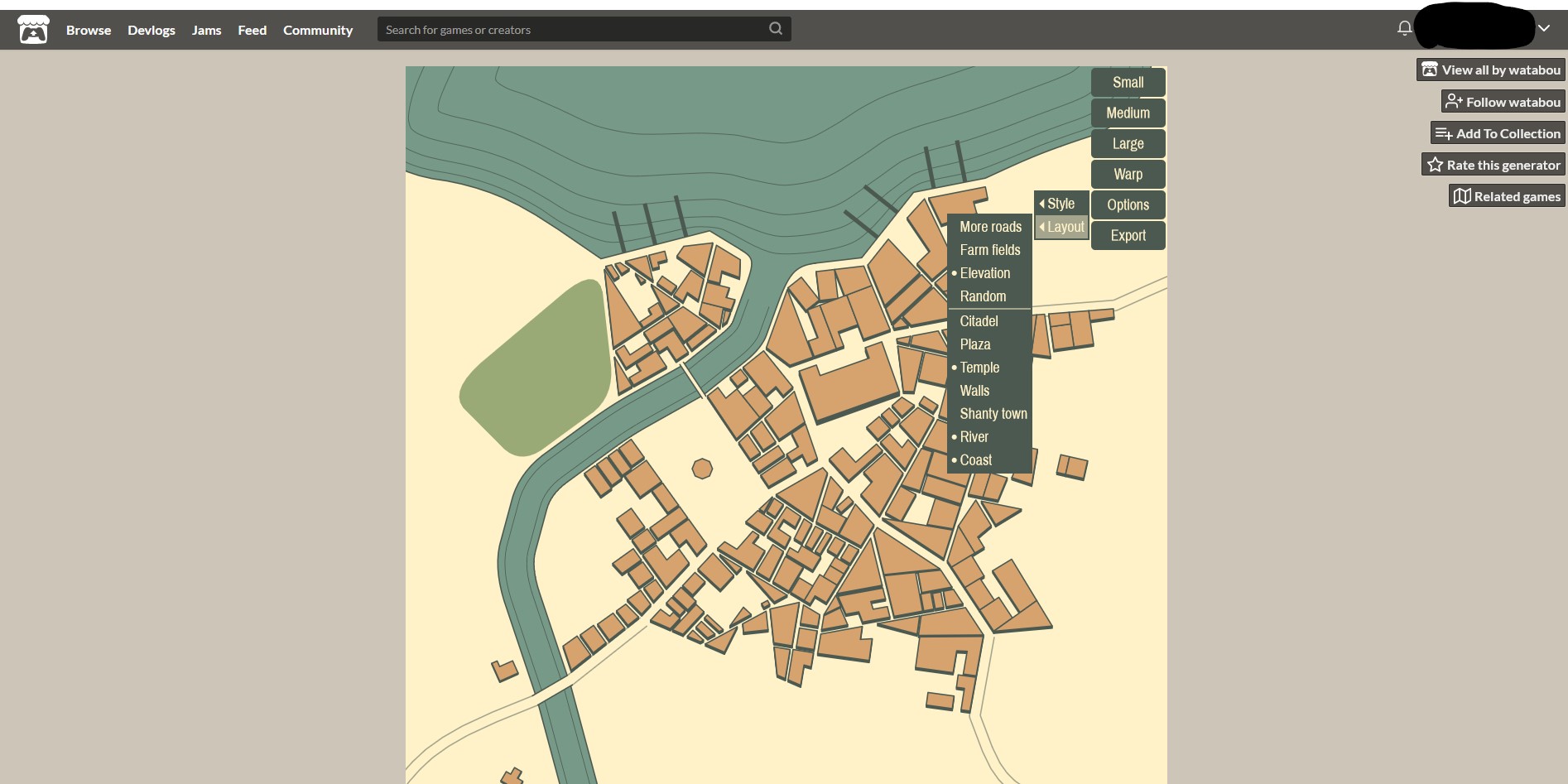

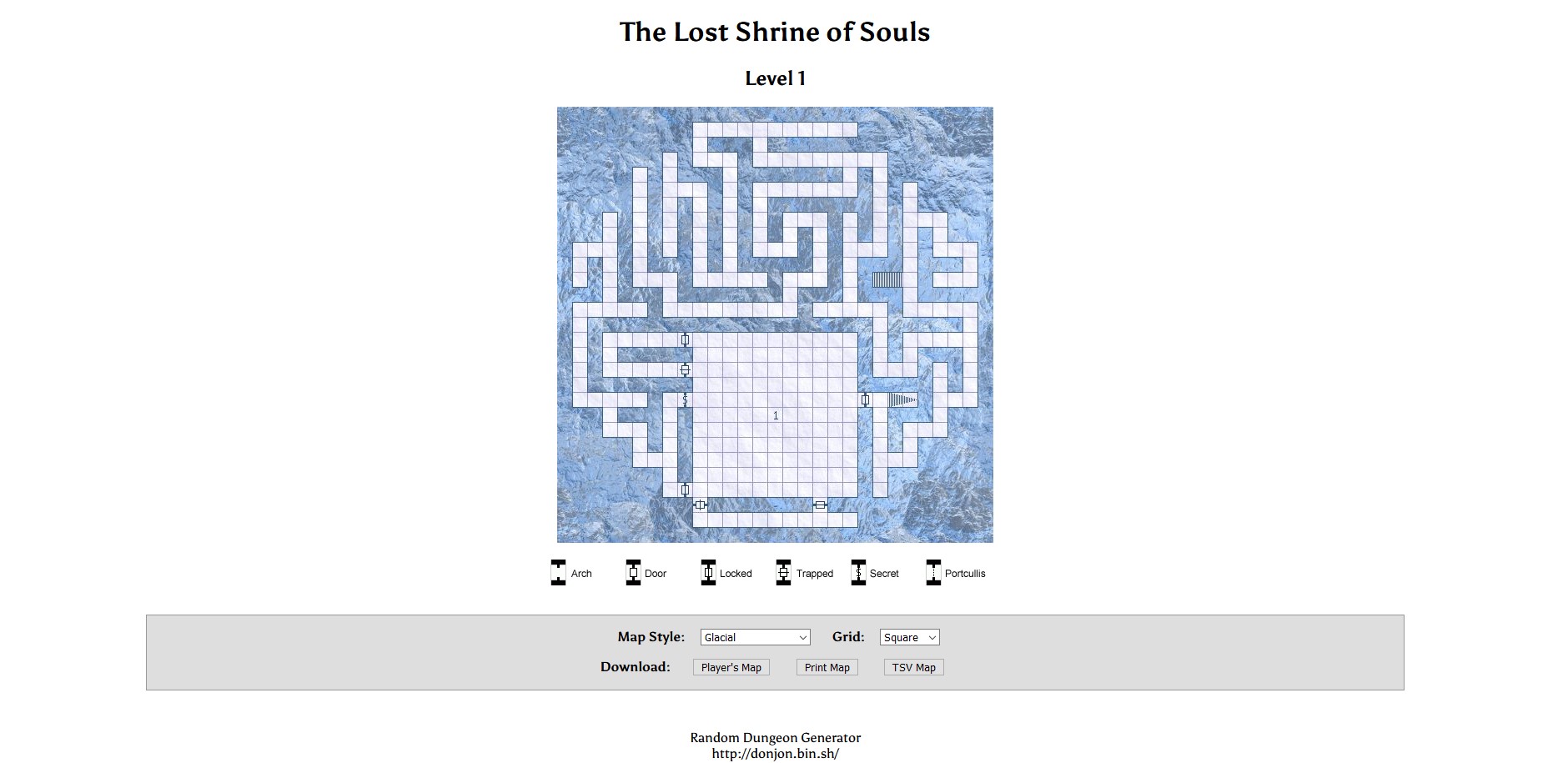

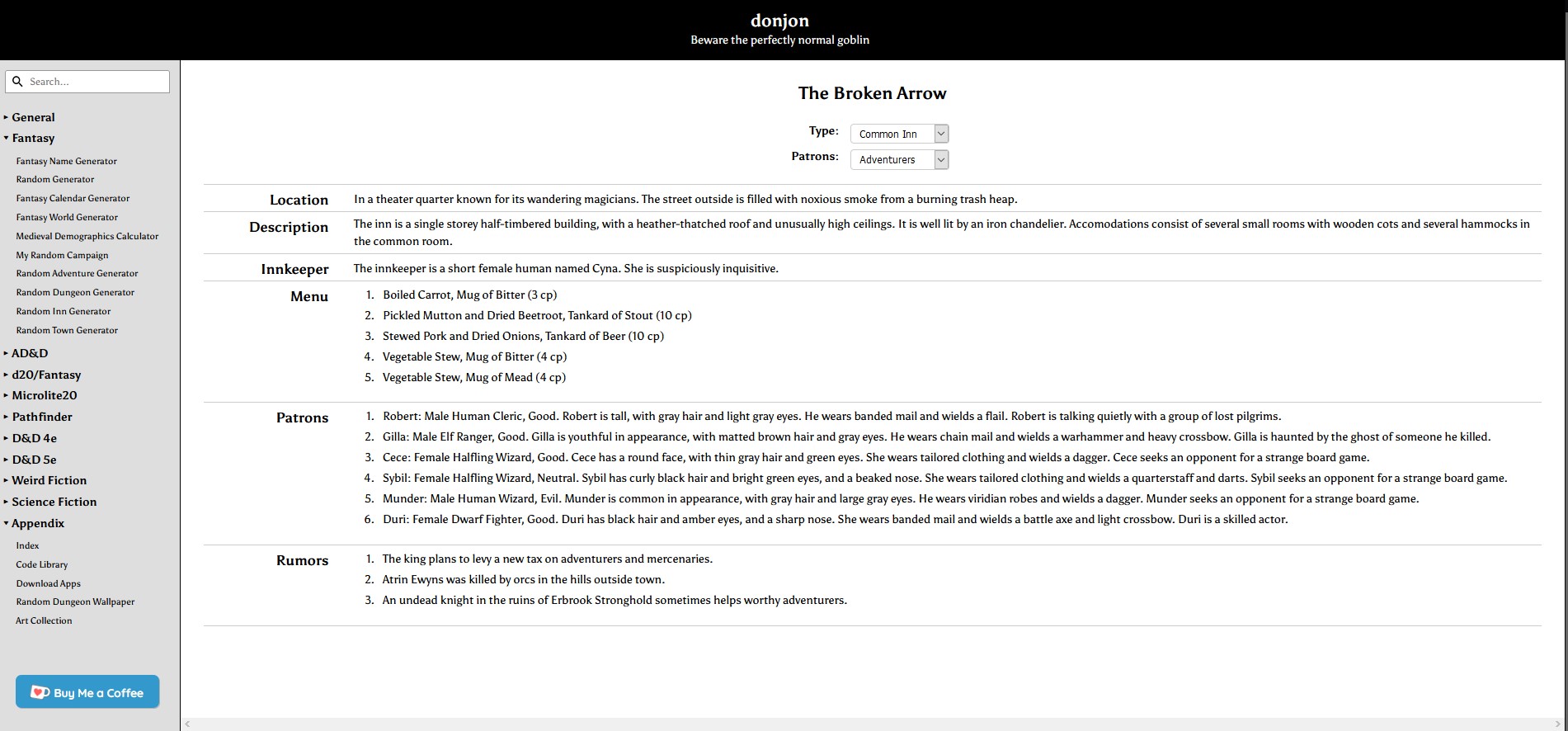

Other things that I’ve done in preparation outside of just reading the book has involved making generic encounter maps for the frozen wasteland of Icewind Dale, along with listening to well over a hundred instrumental pieces of music and “soundscapes,” and categorizing them into several different playlists that I can quickly switch between. Is the place they arrived in a happy town? Well I’ll play the happy town songs for them. Is this battle an intense and dramatic one? Got it covered.

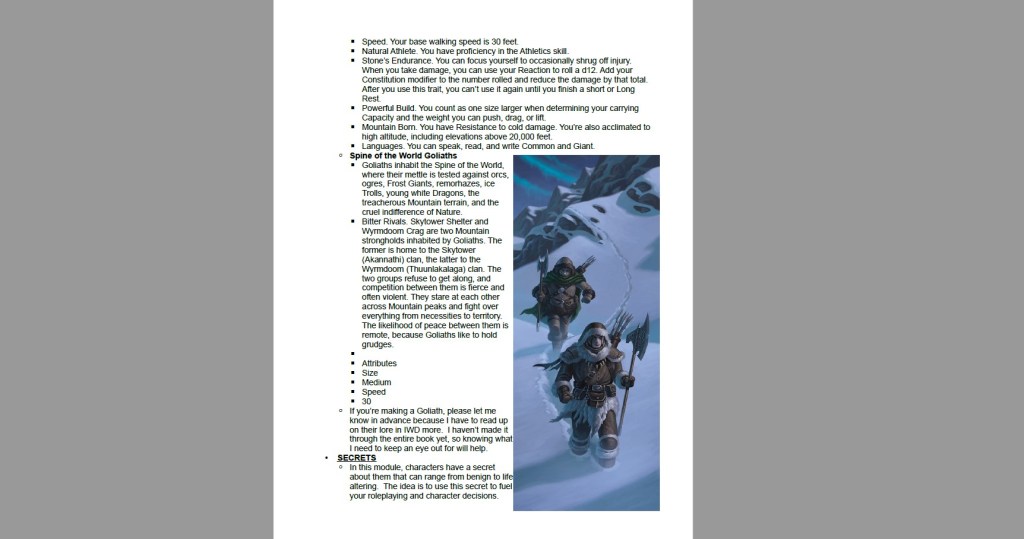

I even went as far as to make a 4-page syllabus of just about everything they need to know in order to create characters for this campaign. When I say that out loud it sounds truly insane, but they genuinely appreciated me doing that. When I’m head down on preparing for campaign, the thought that I might be more “into it” than my players always creeps into my mind, but their reaction to getting a literal syllabus was overwhelmingly encouraging.

All of the little seemingly superfluous things I’ve done in preparation I do because I know that it’s worth it. I can describe a battle in the middle of the frozen wasteland just fine, but having a generic snow-covered battle map I can toss up for them will help give them a sense of place and another opportunity to tangibly interact with their characters. Picking out hundreds of music tracks and categorizing them by their “emotional weight” seems ridiculous, but music is so damn important to setting the tone and atmosphere that I find it’s necessary to a successful campaign.

Maybe this article is just going to be met with other Dungeon Masters feeling like I’ve just described what they all do all the time, but to me I feel like I’m really putting in the extra effort to make this campaign a success. Like I said, this is my first time truly preparing for something this large and intricate, and I don’t want to mess it up. Luckily my players seem just as excited for this new campaign as I am, so I don’t think my efforts will go unnoticed.