A YouTube channel named NoClip, recently released a documentary series about the rebooted Hitman games of the past few years. It highlighted developer IO Interactive and their separation from Square Enix, the way they designed their levels and AI patterns, as well as some other very interesting tidbits about their struggles and accomplishments. You should check it out. But it got me thinking about another stealth-action franchise that could use the same rebooting treatment that Hitman received. Of course I’m speaking of Splinter Cell.

Just like the Hitman franchise, Splinter Cell has had some really good entries in the series, and some not so great ones. Hitman eventually pivoted off of a divisive release in the form of Hitman Absolution, into the phenomenal Hitman 2016. Absolution was a fairly linear game that tried to follow in the steps of popular action games of the time, ultimately betraying the core conceit of what those games were traditionally like. Hitman 2016 threw linearity out the window and placed you into clockwork, systems driven levels that had dozens of way to approach them, with multiple objectives for you to complete, a bevy of disguises and weapons at your disposal, and plenty of over-the-top methods for you to dispatch your targets.

But it isn’t the only tried and true stealth-action franchise that made drastic changes to the formula. In a similar fashion, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain did something of a soft reboot in terms of its mechanics and play style, favoring an open world and systemic driven design as opposed to a more curated one. It wasn’t without it’s issues, but most people can agree that it was the best playing Metal Gear, despite having a middling story at best.

So I got to thinking, if Hitman and Metal Gear could reboot themselves so successfully, Splinter Cell should be able to as well. While it’s easy to say that Splinter Cell should just do the same thing those games did, it can’t. There are fundamental differences in the way those games play that just don’t translate perfectly. But if we were to cherry pick elements from either of those games to slot into a new Splinter Cell, I bet you’d come back with something pretty good.

In Hitman 2016, you’re infiltrating these massive and mostly public spaces, adopting the persona and disguise of whomever you need to be in order to gain access to some of the more guarded targets. You’re usually trying to get rid of some sleazy rich guy who’s throwing a party or staying at a hotel or something. There are more “public” spaces for you to occupy and plan around, making it feel more like a puzzle game than anything else.

In Metal Gear Solid V, you’re infiltrating various military installments spread throughout this massive open world, returning to your home base every so often to cash in your missions or progress the story. There isn’t a ton of variety in the way you actually approach these missions, but you’ve got a pretty impressive tool kit at your disposal, from a rocket powered arm that you can shoot into the faces of your enemies, to a dog that wields a knife in its mouth and will cut fools up at your behest.

Splinter Cell is different kind of game in those regards, striving to be a more grounded depiction of military efficacy than the other stealth-action franchises. That established ideology about what those games do makes it difficult to open up the floodgates and allow for more of the weird shenanigans that Metal Gear and Hitman allow for, and Sam Fisher as a protagonist isn’t exactly the “dressing up like a clown and sneaking into a birthday party” type of secret agent.

But despite all of that, here are some elements from both Metal Gear and Hitman that a new Splinter Cell should implement in a new entry.

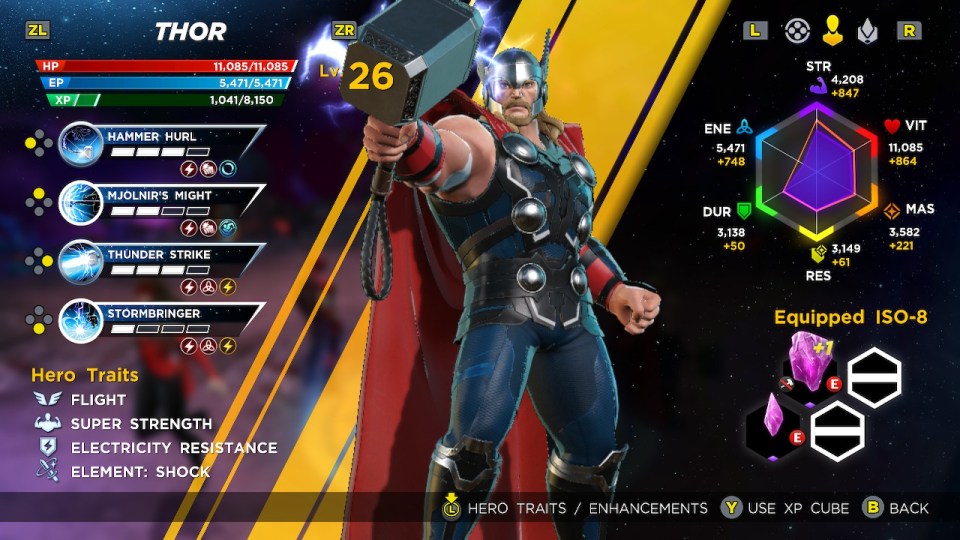

LEVEL DESIGN

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61824071/hitman_2_miami_1.0.jpg)

The star of the modern Hitman games is most certainly the levels that you play in. What Hitman 2016 doubled-down on were these clockwork levels that were massive sandboxes for you to explore, where NPCs had routines and goals for you to intercept and take advantage of. Almost every corner of the level provided you with some new opportunity, tool or costume for you to use to dispatch your targets. Along with that, the way the AI was scripted was such that no matter what you did or who you removed from the world, the game was able to pick it back up and make sure everything didn’t grind to a halt because you killed a particular NPC or were caught doing something.

I think that same philosophy can be applied to Splinter Cell in an extremely effective way. In Hitman, the levels all provide Agent 47 with opportunities to hide in plain sight, playing to his strengths while also providing you with a ton of variety in terms of settings and weaponry. Because Agent 47 is more focused on infiltration, the levels can be anything from an active movie studio, to the suburbs, or to a fashion show. That’s the beauty behind the core concept of Hitman.

Whereas Sam Fisher is more of a traditional spy, running military ops, sticking to the shadows and using his environment to help shield him from detection. Instead of the normal, shoot out the lights and sneak up behind a guy routine, a bigger and more complex level could afford you new opportunities to take when stalking your prey.

The problem is that Sam Fisher as a character has a pretty one-note arsenal. He’s a super effective spy who knows how to sneak around, shoot guns and climb obstacles, but he can never dress up like a hipster and pretends to be the drummer in a band so he can kill the lead singer. It’s what makes creating these more intricate levels so difficult, because nobody ever cares how Sam Fisher gets into an enemy base and kills everyone, because he’s on a mission to a dangerous place where there are rarely any civilians to worry about.

CHALLENGES

There are so many things that make Hitman levels so infinitely re-playable, but the challenges and missions have to be up there. Hitman encourages you to replay levels and approach them differently by rewarding you with experience for throwing a pair of scissors at your target’s head while dressed like a clown, or by pushing a loud speaker off the awning above them and crushing them. By completing these challenges, you’re rewarded with new outfits, starting points, and weapons you can use to flex your creativity. It’s a brilliant loop that consistently proves to be the voice in your head that says, “yeah that was cool, but how about this?”

In Splinter Cell though, you have maybe 3 or 4 ways to actually deal with your targets, and in reality you’re only going to either shoot them or strangle them. That’s kind of another big problem Splinter Cell runs into if it tries to adopt a more Hitman-like approach. How do you encourage your players to play differently, and what does that even look like? Sam Fisher doesn’t dress up in goofy outfits and he rarely hides in plain sight, so how do you make new challenges and missions within this limited tool set as well as what the audience expects from a Splinter Cell game? Without completely redefining what kind of character Sam Fisher is you get kind of locked into a box.

I personally wouldn’t mind seeing an all new Sam Fisher who gets tasked with taking down targets that aren’t purely enemy combatants, but I think people would lose their minds if he suddenly started dressing up as a waiter or something.

WEAPONRY

Some of the deadliest and most effective weapons in Hitman are often the most innocuous ones. I’ve killed more people with pasta cans, letter openers, and cheeseburgers than actual guns, because in Hitman, everything you can pick up becomes a deadly weapon. I’m willing to bet Sam Fisher is just as effective as Agent 47 when it comes to improvised weaponry, but I can’t really recall him ever exhibiting that beyond throwing a brick or a rock.

This issue seems far more surmountable than the previous ones considering that you can put plenty of flotsam and jetsam in the levels that Sam could throw at the heads of his enemies. Cinder-blocks, bottles and so on and so forth all would narratively fit in the self-serious tone of Splinter Cell. But that tone can be a little limiting in terms of what you can cram into a new Splinter Cell.

I want to see Sam Fisher try to play guitar poorly in an attempt to fool his target. Then, when he realizes that the target isn’t buying it, smashes it over their head. He might then say something like, “everyone’s a critic” and move to leave the level. But I sincerely doubt I’d ever see that.

TONE

Speaking of the self-seriousness of the franchise, we arrive at my last point. The tone of Splinter Cell, hell, the tone of all the Tom Clancy games are just so painfully self serious. That isn’t to say that striking a serious tone is a bad thing, but it is limiting if you’re trying to build out levels, opportunities and basically everything I’ve mentioned up until this point.

Even when you look at something like Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, a game that also provided players a systems driven sandbox to skulk around in, that game still had levity built into it. By Metal Gear standards it was pretty serious, but you could still do some wild stuff in that game like making your horse poop on command that would lighten the mood.

I can’t really recall anything like that happening in the Splinter Cell franchise. Sam Fisher will make the occasional quip, but he’s never drowning his targets in the toilet they’re vomiting into like you can in Hitman or confusing enemy guards with 20 inflatable dummies of himself like you do in Metal Gear.

The Tom Clancy approach to things is to make bad military humor that is funny to maybe a handful of people out there. Like, there had to be one person out there who cracked up every time a character shouted the phrase, “shitballs!” in Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon Wildlands, right?

Despite my personal preference for a lighter toned game, I just think that from a design perspective it has to be easier to create fun opportunities than just the standard military fare ones. I’d rather watch the ejector seat on a jet launch a man into the sun than see a guy just shoot a guy with a sniper rifle. It’s why I appreciate the Hitman games so much. Maybe Splinter Cell just isn’t the franchise for me anymore, but if I had my way, it would be a much different game in tone.

I desperately want a new Splinter Cell game, but as time goes on I get a little more cautious about what that game looks like. Between the need to change and the desire to stay true to the existing formulas, I’d have to imagine that part of why a new Splinter Cell hasn’t been announced is because the well of ideas that exists within those confines might be running dry. I just hope that if there ever is a new Splinter Cell game, whatever it turns out to be, it manages to keep me playing for as long as the Hitman reboots have.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61824071/hitman_2_miami_1.0.jpg)